Gradient Descent in practice

Contents

Gradient Descent in practice#

How to choose a correct learning rate?

Short answer: inspect your gradient descent cost function.

Long answer:

Adjusting the learning rate#

It is always a good programming practice to add in your code printouts, i.e. print() statements to inspect the current values of your variables.

In gradient descent, it is advised to print the values of the parameters and the cost function after some iterations. Here is an example of printouts of simple linear regression showing the values of updated parameters \(\theta\) every 10 epochs until \(N\) = 100, then every 100 epochs:

Starting gradient descent

Iteration 10 theta_0 = 23.360 Diff = -0.2486 theta_1 = 1.158 Diff = -0.5069 Cost = 34.1274

Iteration 20 theta_0 = 21.784 Diff = -0.1703 theta_1 = 1.590 Diff = -0.0918 Cost = 27.7958

Iteration 30 theta_0 = 20.339 Diff = -0.1423 theta_1 = 1.847 Diff = -0.0041 Cost = 23.4581

Iteration 40 theta_0 = 19.028 Diff = -0.1262 theta_1 = 2.052 Diff = 0.0133 Cost = 19.9476

Iteration 50 theta_0 = 17.841 Diff = -0.1136 theta_1 = 2.230 Diff = 0.0157 Cost = 17.0769

Iteration 60 theta_0 = 16.767 Diff = -0.1027 theta_1 = 2.390 Diff = 0.0150 Cost = 14.7278

Iteration 70 theta_0 = 15.795 Diff = -0.0929 theta_1 = 2.535 Diff = 0.0138 Cost = 12.8055

Iteration 80 theta_0 = 14.916 Diff = -0.0840 theta_1 = 2.666 Diff = 0.0125 Cost = 11.2325

Iteration 90 theta_0 = 14.121 Diff = -0.0760 theta_1 = 2.784 Diff = 0.0113 Cost = 9.9453

Iteration 200 theta_0 = 9.083 Diff = -0.0252 theta_1 = 3.534 Diff = 0.0038 Cost = 4.7867

Iteration 300 theta_0 = 7.499 Diff = -0.0093 theta_1 = 3.770 Diff = 0.0014 Cost = 4.2340

Iteration 400 theta_0 = 6.917 Diff = -0.0034 theta_1 = 3.856 Diff = 0.0005 Cost = 4.1596

Iteration 500 theta_0 = 6.704 Diff = -0.0012 theta_1 = 3.888 Diff = 0.0002 Cost = 4.1496

Iteration 600 theta_0 = 6.626 Diff = -0.0005 theta_1 = 3.900 Diff = 0.0001 Cost = 4.1483

Iteration 700 theta_0 = 6.597 Diff = -0.0002 theta_1 = 3.904 Diff = 0.0000 Cost = 4.1481

Iteration 800 theta_0 = 6.587 Diff = -0.0001 theta_1 = 3.905 Diff = 0.0000 Cost = 4.1481

Iteration 900 theta_0 = 6.583 Diff = -0.0000 theta_1 = 3.906 Diff = 0.0000 Cost = 4.1480

Iteration 1000 theta_0 = 6.581 Diff = -0.0000 theta_1 = 3.906 Diff = 0.0000 Cost = 4.1480

End of gradient descent after 1000 iterations

Picking a learning rate is a guess’n’check business.

Typical learning rates are between \(1\) and \(10^{-7}\). The common practice is to start with e.g. \(\alpha = 0.01\), a reasonable number of epochs, e.g. \(N = 100\) or \(1000\) (depending on the size of the data set), and see how the gradient descent behaves.

The cost function should decrease after every iteration. If the printouts show that the cost function and parameter are taking very, very large values: \(\alpha\) is too big, the gradient descent is diverging! One should reduce the learning rate by e.g. a factor 10 and see how the gradient behaves.

If the cost decreases after each iteration, this is a good sign that the gradient will converge. However it can converge very slowly if \(\alpha\) is too small, and as a consequence necessitate a large number of epoch before reaching the optimized parameter values. While tuning the hyperparameters, it is generally good to cap the number of epochs low and inspect the difference \(\Delta \theta = \theta^\text{new} - \theta^\text{prev}\) to see if the relative increment or decrement with respect to the \(\theta\) value is small. There is a bit of tweaking before finding a correct learning rate.

A graph to visualize the cost’s evolution#

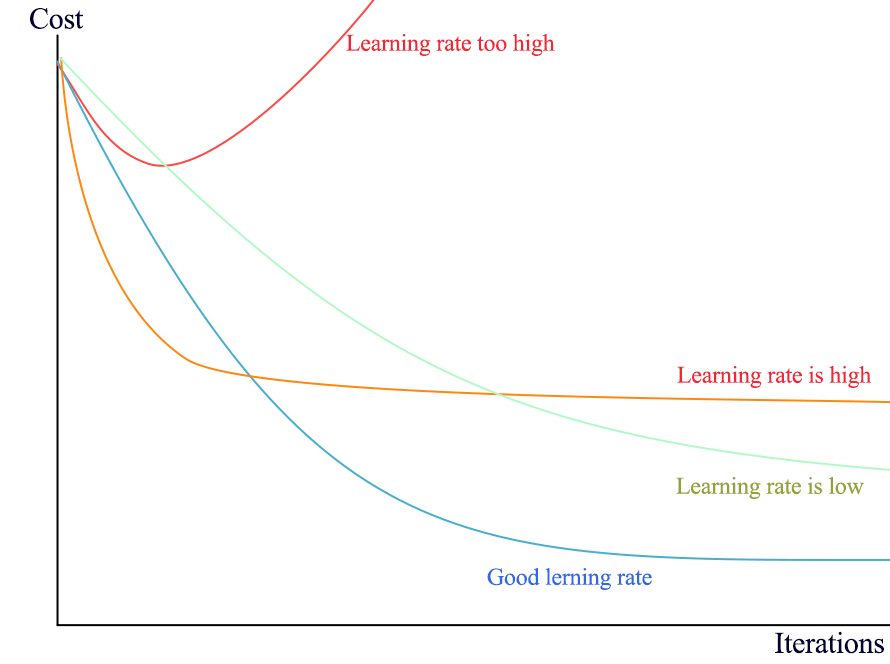

To inspect the gradient descent algorithm, it is convenient to store the intermediary values of the cost function and plot them with the iteration number on the \(x\) axis. The resulting curve should be strictly decreasing. Below is an example with different learning rates being plotted:

Fig. 17 . The learning rate plays a crucial role on the gradient’s speed towards convergence.

Credits: Jonathan Hui Medium#

Exercise

For each learning rate situation above, illustrate with a plot (qualitative drawing) the corresponding evolution of \(\theta\) parameters.

Knowing when to stop#

In mathematics, zero is exactly zero. In computing, variables can store very small numbers considered zero but with trailing non-zero digits. A good cutoff to declare the gradient descent algorithm successful is to exit when e.g. the cost function’s relative decrease is lower than a given threshold, for instance \(10^{-6}\).

Summary

Linear Regression is the procedure that estimate a real-valued dependent variable (target) from independent variables (input features) assuming a linear relationship between \(n\) input features and \(n+1\) coefficients (parameters, or weight). The extra one is the offset parameter.

The cost function computes the sum of errors between the predicted line and the data. It usually uses the least squared method (errors squared).

The Gradient Descent is an optimization algorithm consisting of an iterative procedure to update the parameters in the direction of ‘descending gradient’, i.e. dictated by the slope of the cost function’s partial derivatives for each parameter, until convergence to values for the parameters minimizing the cost function.

Hyperparameters are quantitative entities controlling the learning algorithm.

The learning rate for gradient descent is an important hyperparameter that should be tuned to avoid divergence or over-shooting (learning rate too large) or slow convergence (learning rate too small) necessitating a high number of iterations (epochs).

The linear regression was our starting model. Later in this course, we will see more complex machine learning algorithms able to model non-linear behaviour. Linearity is an assumption that should be made with care.

Fig. 18 . A questionable linear extrapolation, from the great webcomic xkcd.#