From detectors to publications

Contents

From detectors to publications#

How do we gain knowledge about the Universe in experimental particle physics?

This interrogation intrigued me so much that it got me to do a Ph.D. to answer the question.

Note

Experimental particle physics is only the context of this machine learning course, from which examples will be taken. This section is not a physics lecture, rather an introductory tour in the subatomic world. It aims at:

expanding your knowledge in a new area of mathematical sciences

showing how much maths and computing is behind the discipline

presenting the opportunities to contribute to this field

What is particle physics?#

The goal of physics is to understand the universe. Quite a task. Among the numerous branches of physics, particle physics focuses on the tiniest chuncks of matter: elementary particles. It describes how the known elementary particles interact through three of the four fundamental forces, or interactions: electromagnetism, weak interaction and strong interactions. What about gravity? The great Albert Einstein tried to include it until his death without success; merging the theories of Quantum Mechanics and General Relativity is still one of the hardest physics problem today.

So you got the spoiler alert: the theory of particle physics, bearing the weird name of “Standard Model,” is not complete as it does not include all fundamental interactions. Despite this important caveat, the model is a triumphant achievement made by many great physicists since the 1950s (with a large fraction becoming Physics Nobel Prize laureates). Not only does the theoretial framework accurately describe the known subatomic world, it has also accumulated remarkable successes with numerous predictions verified in experiments at an incredible level of precision.

Theoretical vs experimental particle physics#

In all physical sciences, knowledge is forged via the process known as the scientific method.

In-class exercise

Take 5 min to define the scientific method. Write full sentences or keywords in a bullet list. Then compare with your neighbours your definition. What notion(s) did you put that they omitted? What did you miss? Form a merged definition with two or three classmates.

In particle physics there has always been a back-and-forth between theory and experiments. Either a new particle is discovered and no one understand why. It was the case in 1936 with the discovery of the muon, a heavier cousin of the electron. It surprised the community so much that Nobel laureate Isaac Rabi famously quipped: “Who ordered that?” The other way around is more common: the model provides a prediction, usually in the form of a new particle or a new process (particle interaction) that can be observed in the data from particle detectors. The theory of particle physics has drawn its succcess from the numerous experimental confirmations of theoretical predictions, with mind-blowing precision at the part-per-billion level.

State-of-the-art machines#

Often a conceptualized new particle would require several decades for the experimental setup to be ready, as its observation demands a higher energy beam, a finer resolution or both. In that sense, particle physicists works hand-in-hand with engineers towards pushing the limits of technology. The quest of one particle is remarkable; the Higgs boson was a missing piece in the Standard Model, responsible of giving to other particles their respective masses. It took 48 years between its formulation in 1964 and the discovery in 2012 at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at the European Organization for Nuclear Research near Geneva, Switzerland. The LHC is one of the most complex machines ever built by human beings and collects several superlatives. I happen to work on another endeavour, currently under construction, called the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE). It will demands a newer generation of detectors due to the size and the intensity of the incoming beam. Unique challenges lie ahead for this future biggest neutrino detector in the world, especially in computing. Due to enormous physical data volumes that need to be acquired, stored and analyzed, the requirements of DUNE is likely to trigger a paradigm shift with groundbreaking new techniques in data science.

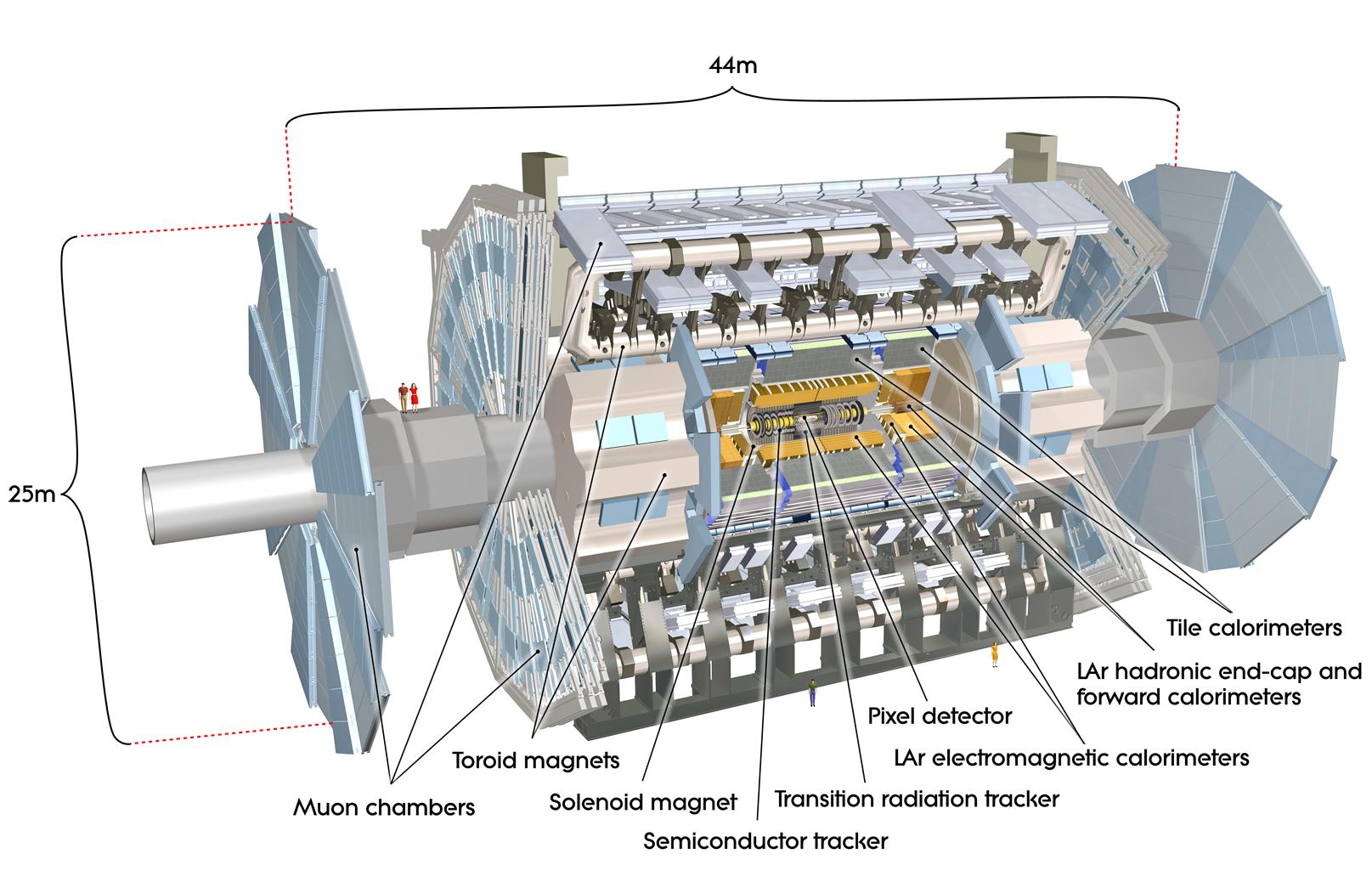

Fig. 1 . Schematic of the ATLAS detector with its subsystem. People (who are not allowed to climb by the way) are drawn for scale. ATLAS is the largest volume detector ever constructed for a particle collider. You can take a virtual tour here.

Credits: ATLAS Experiment © 2021 CERN.#

Many activities, many people#

Particle physics is a discipline offering a wide range of sub-activities, in particular on the experimental side. On the data analysis side, the numerous steps and various associated tasks will be covered in the coming section How do we analyse data?. It is also possible to contribute in hardware projects, such as test beam campaigns and detector upgrade programs. Getting to design, test or build the next generation of particle detectors can be very exciting! Many simulations are required, so even on this hardware and engineering related side, mathematicians and programmers can help. At the interface between hardware and software lies data acquisition. Experts here (engineers and also physicists) ensure the microelectronics are proper to deliver quality data in due time. If you think this is not where machine learning techniques would operate, hold on: very recent multi-disciplinary proposals are eager to implement machine learning algorithms on programmable hardware for pattern recognition! This would enable pattern recognition and particle identification to operate ‘live’, i.e. during data taking. Many particle physics experiments are eager to implement these fast techniques in order to know as soon as possible if the fresh data contains interesting physics or not.

Learn more

A programmable hardware is an integrated circuit with configurable logic blocks that can be wired together using a special software. The most popular programmable logic device is the field-programmable gate array (FPGA). It is widely used in particle physics experiments as well as in other electronics applications. Yet programming machine learning algorithms on FPGAs (labelled ML-FPGA) is a new effort that, due to the requirements in particle physics, is very promising.

Further readings on hardware acceleration

Specific to particle physics: (and a bit technical) Particle identification and tracking in real time using Machine Learning on FPGA.

Nowadays, most particle physics endeavours can not be achieved alone. The magnitude of the experiments, their complexity and the resulting workload require a highly collaborative and international environment. For instance the ATLAS Collaboration, associated with the largest general-purpose particle detector experiment at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), comprises over 5900 physicists, engineers, technicians, students and administrators. ATLAS has 2900 scientific authors from over 180 institutions. It is one of the largest collaborative efforts ever attempted in science. The more recent DUNE Collaboration has already 1400 members and is growing.

Spin-offs#

In the quest to better understand the universe, particle physics has created by-products and even new disciplines, some drastically changing our lives. One striking example is the World Wide Web, invented at CERN by computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee in 1989. At the start, the so-called HTTP protocol and first web server were a mean to manage documentation. A couple of years later, this seamless network that any computer would be able to access revolutionized the way information was shared and the way we communicate, socialize, and conduct business.

Particle physics brought several breakthrough technology in medical physics, a branch of applied physics which has emerged since the discovery of x-rays by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895. In the 1950s a detector called Position Emission Tomography (PET) was used to visualize inside the body, from metabolic processes to tumorous cells. Years later, driven by the technical challenges posed by the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, innovative material and chip design used in state-of-the-art LHC detectors were implemented in PET prototypes to increase their resolution. This was imaging for diagnosis. Another technology-transfer arising from the development of linear accelerators was radiotherapy: the beam of accelerated particles is directed into the patient’s body to kill tumor tissue.

Learn more

Articles about CERN’s activities benefiting medical physics:

How do we analyse data?#

Back to our original question.

Although the data and physics outcomes are different between the various particle detectors, there is a common series of steps shared in data analyses.

The raw data from particle detectors is a (large) collection of activated electronic channels from the detector’s readout material. Such readout material can be an array of wires, or sensitive plates, usually in a high number to cover a large area or volume, similar to tiles covering a rooftop.

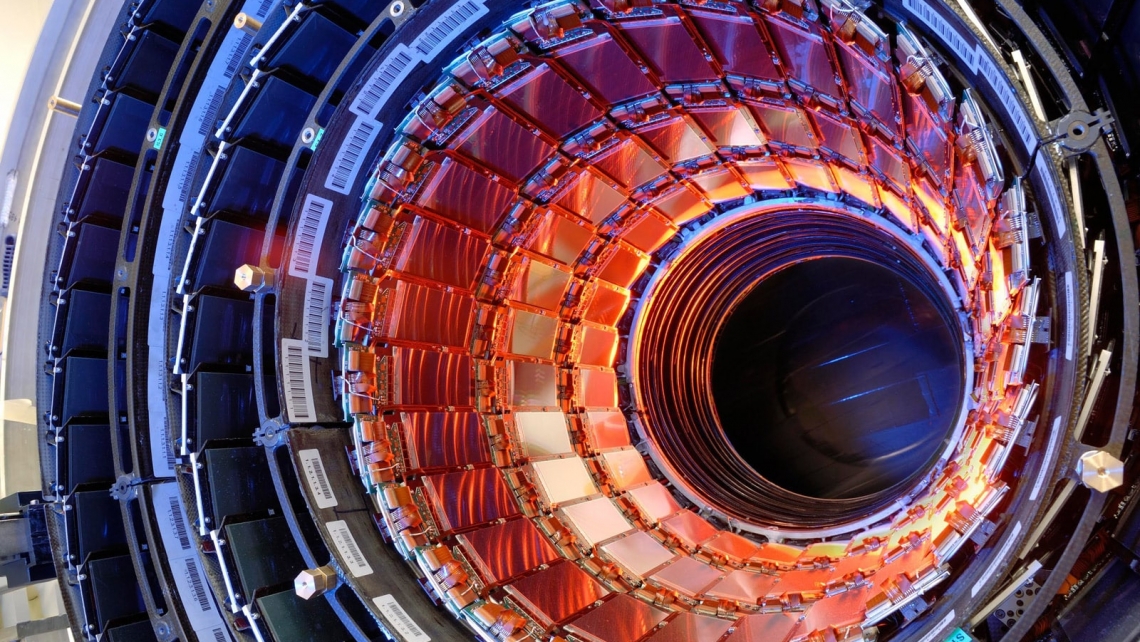

Fig. 2 . The tracker of the CMS experiment, one of the detectors of the LHC ring.

Credits: CMS Experiment © 2021 CERN.#

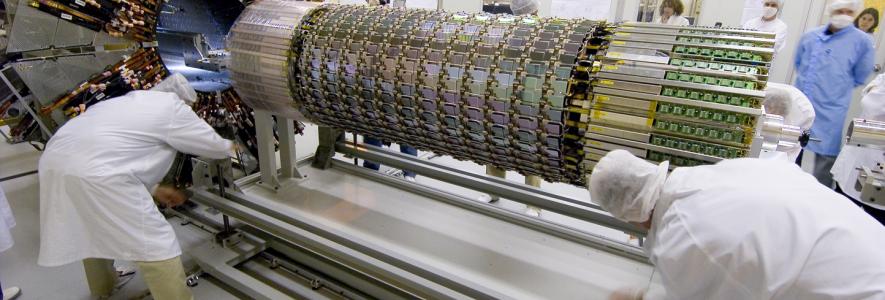

Fig. 3 . Workers assembling the ATLAS SemiConductor Tracker (SCT) at CERN.

Credits: ATLAS Experiment © 2021 CERN.#

1. The trigger#

When particles with sufficient energy pass through the wires or plates, a current is produced and picked up by the electronics. If several adjacent wires or plates are activated at the same time, chances are, an interesting particle interaction has taken place. The first step at the start of the data acquisition is the trigger: a combination of hardware and software selects the most interesting interactions for study.

A particle detector is analogous to a camera: it takes ‘pictures’ of interactions of interest. Two important points:

The interactions of interest are usually not alone. Either there is a mess of other particles produced - that is the case in colliders with man-made energetic collisions. Alternatively, detector expecting rare signals can have impurities in them causing noisy interactions mimicking the ones physicists are looking for. We refer to these unwanted events as background, opposed to the signal, the interactions we want to record and analyse later.

The pictures are not common pictures, they need post-processing, i.e. the 3D interaction needs to be ‘reconstructed.’

A recorded interaction is labelled an ‘event.’ It is an undeveloped photography. As we don’t know yet which particles are at play, we collect a very large amount of events that will be pre-processed and later analyzed statistically.

2. Event reconstruction#

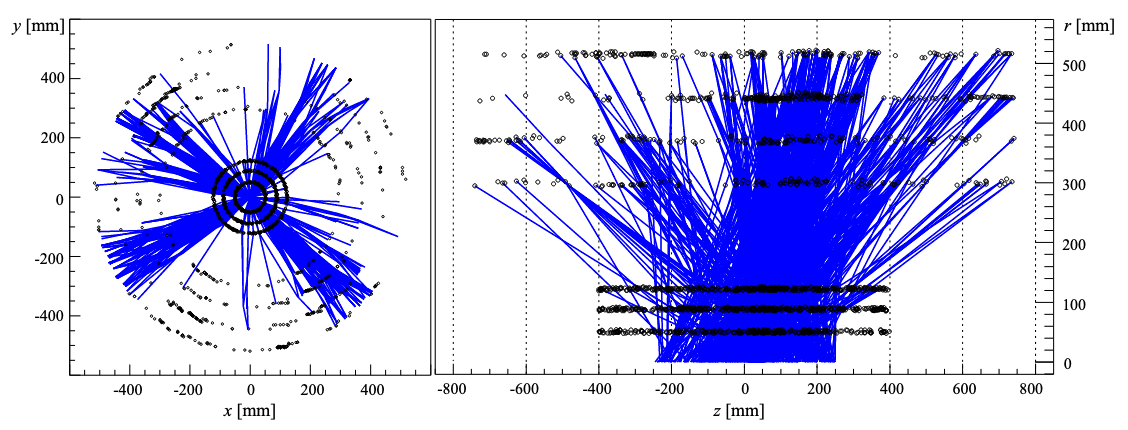

As stated above, a raw event contains all the triggered electronics from the numerous wires or planes of all sub-detector systems. To put it in mathematical terms: it is a large collection of dots, with their coordinates and a timestamp. It is impossible to visualize as-is nor start any data analysis yet. The reconstruction step is necessary to create more visual entities such as tracks representing the particle trajectories.

Fig. 4 . Front and side view of the cylindrical ATLAS inner detector with recorded hits (dots) and candidate tracks (blue). Credit: Andreas Salzburger.#

Algorithms are given as input all dots coordinates and work out the best combination to draw tracks connecting them. At the end, the data from a given event contains a bunch of tracks, which can be straight or curved, vertices, which are intersections between tracks, and the amount of ‘deposited energy’, that is to say the energy the particle put into a special readout material while slowing down, giving us access to its initial energy (crucial for the particle’s identification).

3. Particle identification#

With the tracks, vertices and deposited energy information, it is possible to identify the different particles that were present in that given event, with even their initial speed and direction right after the interaction in which they were produced. Many different algorithms are employed at this stage, all specific to the particle they aim at identifying. A lot of those algorithms use machine learning techniques. At the end of the particle identification step, the information we have can be illustrated as a 3D rendering (you can see an example here I can detail to you if you are curious).

4. The comparison#

At this stage we have a picture of the interaction’s detected ‘objects’, i.e. the identified particles, their energy and direction from the moment they were produced. But these objects are usually the secondary products of the interaction of interest. Most key particles are decaying shortly after being produced without even reaching the detector’s readout material. Consequence? With a single picture of the detected products of an interaction, we can not know which initial particles were present. Moreover, known processes are often producing the same secondary products. The only way we can know is statistical, by collecting many of these and seeing the trends between the signal (the process we want as predicted by theorists) and the known mimicking processes we don’t know, aka the background (sometimes referred as noise in other fields). We know the signal and background trends using simulated samples: it looks like the data but the interactions were generated by dedicated algorithms.

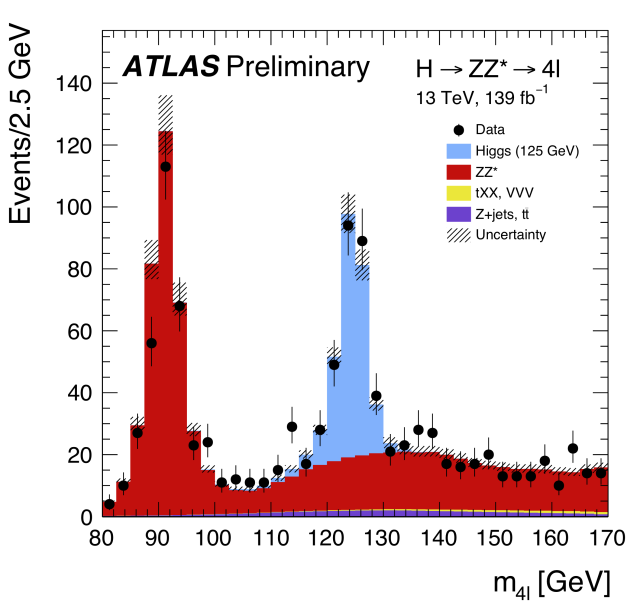

In both real and simulated data, we compute special entities, quantifying the topology of the recorded objects from the interaction. For instance, it can be the norm of the vectorial sum of two particles’ speed vector. To visualize the trends, we plot the data as histograms to see how the variable is distributed in a given range of values for both signal and background. After numerous studies using other variables, checks and more checks, we can overlay two distributions:

the background and signal distributions, indicating the number of predicted events (vertical axis) for a given range of the plotted variable (horizontal axis).

the real data (black dots on the plot below) - remember, we don’t know what’s inside!

Fig. 5 . Overlaid distributions of the data (black dots) with the simulated data (colored filled histograms). The predicted signal process is the Higgs boson in blue, while background processes (red, purple and yellow). The variable \(m_{4l}\) is analogous to a mass. There are two resonances (we call them mass peaks) and you can see that the data points overlay well with the predicted Higgs peak.

Credits: ATLAS Collaboration/CERN.#

5.Statistics takes over#

We are still not done! After many other checks and additional studies, we obtain numbers we can robustly trust. Those are usually the observed number of events in the data and the predicted number of events in simulations (from the known background processes and the signal). The latter comes with unavoidable experimental uncertainties. To provide a scientific answer if a new particle or subatomic interaction is occuring in nature or not, we use statistical inference, a protocol to derive conclusions from the data. In particle physics, we often use a sub-protocol called statistical hypothesis testing. It is specified by a ‘test statistic’, which is a summary, i.e. a single number of the gazillion of measurements from the experiment! There are several types of test statistic; a common (and powerful) test used in particle physics is the so-called log-likelihood ratio.

To claim a discovery in physics, we proceed with care. There are two outcomes while searching for a new particle or interaction: either it exists in nature or it does not. In the former case, we denote it as signal-hypothesis, usually labelled \(H_1\). The latter case corresponds to the null hypothesis, \(H_0\), where the signal we look for does not exist (the data are compatible with the background-only). If we were to show that \(H_1\) is true, how to be sure that this signal corresponds to the theory predicting it? To play safer and reach a scientific conclusion, we proceed the other way around: we show that, given the data, the null hypothesis is not tenable. Rejecting the null hypothesis is done using quantifiers that give us how unlikely the null hypothesis is true. In this sense, physical sciences does not provide a yes-or-no answer. It outputs a number showing how unlikely an outcome is.

6. The conclusion#

When experimentalists compile their findings into a publication summarizing the signal under study, the experimental setup, the observed data and the statistical output, theorists take over by incorporating the results into their models. Before a discovery is claim (and at times before candidate theories are abandonned), it takes numerous complementary analyses, across several experiments, to disprove the current model and replacing it with a new one. Nevertheless, the steps listed above gives a comprehensive overview of how scientific advance is made. This culminates in the updated version of physics textbooks as a testimony of the accretion of knowledge.

The maths and computing in particle physics#

Although the field belongs to physics, a lot of mathematic and computing lie in the exploration of the subatomic world. During this tour I will briefly mention the concepts and show the connections between what you may have learned - or will learn - in pure mathematics and their use in the reality we live in.

Fields, symmetries and groups#

Fig. 6 . Emmy Noether

Einstein wrote she was “the most significant creative mathematical genius thus far produced since the higher education of women began.” Noether had to ask permission to her male professors for attending their lectures and later as professor did not receive any salary.#

The theory of particle physics can be described by group theory. Groups are connected to symmetry, which is a very familiar concept while seeing forms such as squares or circles. In particle physics, symmetries are more abstract. It is easier to picture them as invariance. The invariance in time implies that for instance boiling water on Monday or Wednesday (or any time) will yield the same result. Two particles colliding is invariant in translation and rotations - i.e. the physics will be the same if the entire system is rotated or shifted further away.

An important theorem ruling mathematical physics states that for each invariance or symmetry, there is an associated conserved entity. It was discovered by the great German mathematician Emmy Noether (1882 - 1935) and the theorem bares her name. The time-translation invariance implies conservation of mass-energy. The fact that physical systems behave the same regardless of how they are positioned in space (translation invariance) leads to the conservation of linear momentum.

Noether thus showed that for each symmetry in nature there is an associated conservation law. This is a fundamental theorem in our understanding of physics. In the subatomic domain, there are additional, more abstract symmetries (the technical world is gauge symmetry or gauge invariance). The mathematical formalism behind those abstract symmetries are described by Lie groups. What I find particularly fascinating is the fact that only a subset of Lie groups - technically SU(3)\(\times\)SU(2)\(\times\)U(1) - is describing these gauge symmetries. Our universe is a particular case of theoretical algebraic structure much larger than the special configuration we live in. What about all possible Lie groups? Are there parallel universes ruled by other symmetries?

Phystatisticians#

This portemanteau reveals the skillset expected for experimental particle physicists. As mentioned above in section 5.Statistics takes over, physics analyses require complex statistic tools. As probability rules the quantum world, histogramming is phystatisticians’ main sport. As all collected events (pictures of interaction) by a detector are statistically independent of one another (each collision produce a given process at a constant mean rate), the ruling probability distribution function is the Poisson one. Other distributions useful in physics (non-exhaustive list) are the Breit-Wigner, the Landau distributions and the Crystall-Ball function.

A particle physics analysis demands a good knowledge on how to treat statistical and systematic uncertainties associated with numerous measurements from the various detector components. Combining correlated data is not trivial. The fitting procedures that are an integral part of the test statistics requires dedicated studies and care, and at times custom-made tests such as the CLs method.

Computing#

Fig. 7 . The Tier-0 data centre on CERN’s main site. This is the heart of the Worldwide LHC Computing Grid. Image credit: Roger Claus, CERN.#

Experimental particle physics has been dealing with large amount of data. Nowadays the volumes are in the order of petabytes (1000 terabytes). To give you a sense of what a petabyte is: it corresponds to 3.4 years of 24/7 full high definition video recording (source and other comparisons here). Particle physics has developed tools to store, manage and distribute significant volumes of data.

Future experiments will open the door to the exabyte era (1 exabyte = 1000 petabytes). This would require one million powerful home computers. More efficient, cost-effective software and infrastructure need to be developed. Luckily, we live nowadays in the age of information explosion; Big Data is now a buzzword in other fields of science as well as in industry. As such, many toolkits have emerged, which particle physicists can use and adapt in order to overcome the new computing challenges.

Beside the data volumes, particle physics heavily relies on simulations, and their computing costs are staggering high. Due to the probabilitistic nature of quantum mechanics, such programs rely on stochastic modeling. As the processes to simulate are usually extremely complex with lots of dimensions - a typical collision at the LHC creates hundreds of particles - interaction events cannot be modelled implicitly. The only practical way to simulate interaction is to perform repeated sampling to obtain the statistical properties of the phenomena. This technique is called a Monte Carlo method. The name refers to the iconic gambling place that is the grand casino at Monte Carlo in Monaco, a principality between France and Italy, on the Meditarranea Sea. Monte Carlo Event Generators, as these simulation programs are called, draw random numbers to pick outcomes according to the assumed quantum mechanical probabilities. Particle physicists use several of these programs to model the processes they study, as well as those they look for (with parameters provided by theorists). Monte Carlo techniques are also use in other scientific domains; for instance in biology, it can help simulate an infection spread. In engineering, it can reproduce the phenomenon of particle diffusion within a material.

Today’s landscape in particle physics#

On the theory side#

To put it frankly: we are eagerly awaiting the next Albert Einstein.

The theory of particle physics - called Standard Model - is a brilliant achievement when it comes to describing and predicting what we know about visible matter. But it has inconsistencies. Terrible ones. There are unstabilities we cannot yet explain. Certain particles, the neutrinos for instance, behave very differently from the theory. We know that visible matter is not the full story. It actually represents less that 5% of matter content in the universe! Astronomical observations led to postulate the presence of a mysterious type of matter that is not visible yet there, as we indirectly measure its gravitational effect on visible matter. Dark matter, as it is labelled, makes up approximately 85% of the universe’s total mass. The overwhelming 75%, you may ask, is what cosmologists call ‘dark energy’, a hypothetical form of matter with an anti-gravity effect to explain why our universe’s expansion is accelerating. The names are labels; we have no clue what dark matter and dark energy are made of.

The ongoing quest of researchers in the subatomic world is to find ‘new physics’, that is to say new phenomena going beyond the Standard Model, our current theory.

On the experimental side#

Disclaimer: this list is by far non exhaustive and limited to my areas of expertise. I am happy to provide additional reading on demand.

There are numerous particle physics experiments in the world, some actively recording data, future ones currently under construction and others still on paper awaiting approval.

The Large Hadron Collider at CERN, active since 2010, will have several data taking campaigns until 2038. A special upgrade of the accelerator will enable more intense collisions from 2029, increasing the discovery potential of new phenomena. Pletora of measurements and searches are being performed there with the goal to extend, improve our current understanding.

A sub-branch within particle physics is dedicated to understanding the mysterious neutrino, this shy elementary particle very tiny and hard to catch. Numerous detectors have been built to this end. The one I am part of, the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, or DUNE, is a mega project currently under construction. It is designed to bring conclusive answers on key measurements in the neutrino sector.

The search for dark matter can be done at colliders as well as with dedicated experiments, which are usually underground to shield them from the noisy particle interactions we see at the Earth’s surface. The LUX-ZEPLIN experiment, at the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF) in the United States, became in July 2022 the most sensitive dark matter detector (more)

There are of course many other experiments performed in particle physics laboratories. If you are curious, I listed at the end of this section particle physics magazines and journals that are sharing in simple words the latest findings in the field.

Opportunities for mathematicians and programmers#

Several internships and jobs in particle physics do not ask for a physics degree. This trend tends to strengthen in present times with the increasing complexity and new challenges posed by the next generation of detectors. Machine learning, already popular in the past decades, is invading all aspects of physics analyses, as we will see throughout the lectures. Computer scientists are thus more and more needed to help speed up code, write efficient software and manage ever-growing piles of data. As most physics problems are posed in mathematical language, mathematicians can be an asset for exploring new approaches and a collaboration with physicists is certainly fruitful.

The biggest physics laboratories offer special programs for students curious about the particle adventure.

CERN OpenLab accepts B.Sc. and M.Sc. students in computing science or mathematics

Further links#

If you are curious, here a some resources to expand your knowledge in particle physics.

Online journals and magazines:

Symmetry Magazine reports on the latest news as well as the people behind the science, providing all the background information to enrich your culture of particle physics.

Interactions.org is a communication resource for information about particle physics, in particular press releases (you can get them in your inbox by subscribing to their newsletter).

CERN Courier highlights the latest developments in particle physics, accelerators, detectors and the applications in related fields.

More technical reviews:

Particle Bite is an online particle physics journal club written by graduate students and postdocs. Each post presents an interesting paper in a brief format that is accessible to undergraduate students in the physical sciences who are interested in active research.

Particle Data Group (PDG), an international collaboration that provides a comprehensive reviews written by the world’s experts in particle physics and cosmology.