Gradient Descent in Practice

Contents

Gradient Descent in Practice#

How to choose a correct learning rate?

Short answer: inspect your gradient descent cost function.

Long answer:

Adjusting the learning rate#

It is always a good programming practice to add in your code printouts, i.e. print() statements to inspect the current values of your variables.

In gradient descent, it is advised to print the values of the parameters and the cost function after some iterations. Here is an example of printouts of simple linear regression showing the values of updated parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) every 10 epochs until \(N\) = 100, then every 100 epochs:

Starting gradient descent

Iter 0 θ₀ = 25.130 ∂J/∂θ₀ = -2.5948 θ₁ = 2.146 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -42.9159 Cost = 56.84502

Iter 10 θ₀ = 23.260 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 1.9969 θ₁ = 1.640 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -9.6267 Cost = 33.25208

Iter 20 θ₀ = 21.647 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 2.7424 θ₁ = 1.711 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -2.4181 Cost = 27.31331

Iter 30 θ₀ = 20.205 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 2.6824 θ₁ = 1.889 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.8322 Cost = 23.07411

Iter 40 θ₀ = 18.904 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 2.4700 θ₁ = 2.075 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.4608 Cost = 19.63395

Iter 50 θ₀ = 17.729 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 2.2437 θ₁ = 2.248 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.3540 Cost = 16.82019

Iter 60 θ₀ = 16.665 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 2.0317 θ₁ = 2.406 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.3066 Cost = 14.51773

Iter 70 θ₀ = 15.703 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 1.8383 θ₁ = 2.549 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.2745 Cost = 12.63362

Iter 80 θ₀ = 14.833 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 1.6630 θ₁ = 2.678 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.2477 Cost = 11.09184

Iter 90 θ₀ = 14.045 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 1.5044 θ₁ = 2.795 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.2239 Cost = 9.83019

Iter 100 θ₀ = 13.333 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 1.3609 θ₁ = 2.901 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.2025 Cost = 8.79778

Iter 200 θ₀ = 9.058 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 0.4993 θ₁ = 3.538 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.0743 Cost = 4.77406

Iter 300 θ₀ = 7.490 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 0.1832 θ₁ = 3.771 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.0273 Cost = 4.23233

Iter 400 θ₀ = 6.914 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 0.0672 θ₁ = 3.857 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.0100 Cost = 4.15940

Iter 500 θ₀ = 6.703 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 0.0247 θ₁ = 3.888 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.0037 Cost = 4.14958

Iter 600 θ₀ = 6.625 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 0.0091 θ₁ = 3.900 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.0013 Cost = 4.14825

Iter 700 θ₀ = 6.597 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 0.0033 θ₁ = 3.904 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.0005 Cost = 4.14808

Iter 800 θ₀ = 6.587 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 0.0012 θ₁ = 3.905 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.0002 Cost = 4.14805

Iter 900 θ₀ = 6.583 ∂J/∂θ₀ = 0.0004 θ₁ = 3.906 ∂J/∂θ₁ = -0.0001 Cost = 4.14805

End of gradient descent after 1000 iterations

Picking a learning rate is a guess’n’check business.

Typical learning rates range between \(1\) and \(10^{-7}\). The common practice is to start with e.g. \(\alpha = 0.01\), a reasonable number of epochs, e.g. \(N = 100\) or \(1000\) (depending on the size of the data set), and see how the gradient descent behaves.

The cost function should decrease after every iteration. If the printouts show that the cost function and parameter are taking very, very large values: \(\alpha\) is too big, the gradient descent is diverging! One should reduce the learning rate by e.g. a factor 10 and see how the gradient behaves.

If the cost decreases after each iteration, this is a good sign that the gradient will converge. However it can converge very slowly if \(\alpha\) is too small, and as a consequence necessitate a large number of epoch before reaching the optimized parameter values. While tuning the hyperparameters, it is generally good to cap the number of epochs low and inspect the difference \(\Delta \theta = \theta^\text{new} - \theta^\text{prev}\) to see if the relative increment or decrement with respect to the \(\theta\) value is small. There is a bit of tweaking before finding a correct learning rate.

A graph to visualize the cost’s evolution#

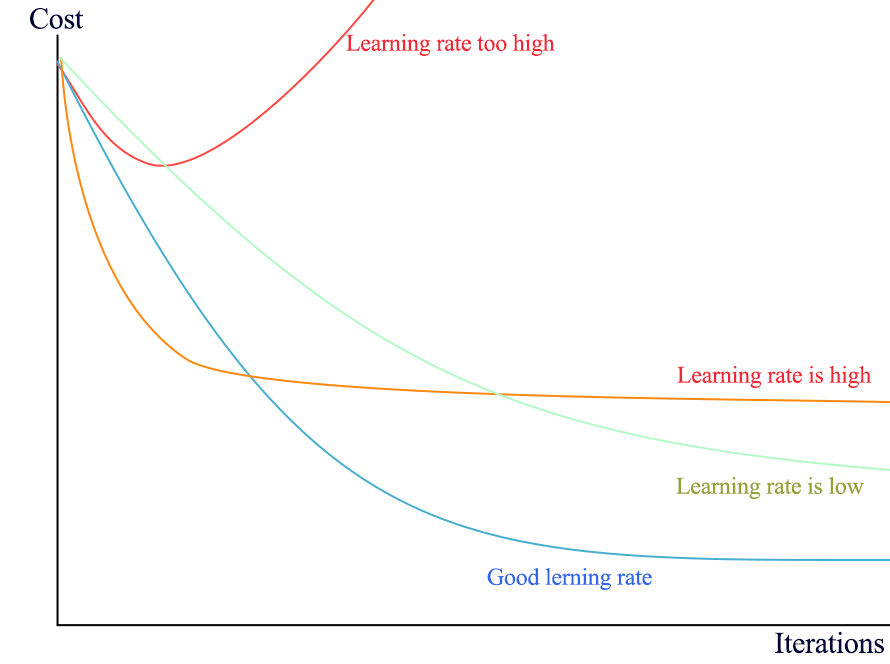

To inspect the gradient descent algorithm, it is convenient to store the intermediary values of the cost function and plot them with the iteration number on the \(x\) axis. The resulting curve should be strictly decreasing. Below is an example with different learning rates being plotted:

Fig. 9 : The learning rate plays a crucial role on the gradient’s speed towards convergence.

Credits: Jonathan Hui Medium#

Exercise

For each learning rate situation above, illustrate with a plot (qualitative drawing) the corresponding evolution of the model parameters.

Knowing when to stop#

In mathematics, zero is exactly zero. In computing, variables can store very small numbers considered zero but with trailing non-zero digits. A good cutoff to declare the gradient descent algorithm successful is to exit when e.g. the cost function’s relative decrease is lower than a given threshold, for instance \(10^{-6}\).

Summary on Linear Regression#

Key concepts

Linear Regression is the procedure that estimate a real-valued dependent variable (target) from independent variables (input features) assuming a linear relationship between \(n\) input features and \(n+1\) coefficients (parameters, or weight). The extra one is the offset parameter.

The cost function computes the sum of errors between the predicted line and the data. It usually uses the least squared method (errors squared).

The Gradient Descent is an optimization algorithm consisting of an iterative procedure to update the parameters in the direction of ‘descending gradient’, i.e. dictated by the slope of the cost function’s partial derivatives for each parameter, until convergence to values for the parameters minimizing the cost function.

Hyperparameters are quantitative entities controlling the learning algorithm.

The learning rate for gradient descent is an important hyperparameter that should be tuned to avoid divergence or over-shooting (learning rate too large) or slow convergence (learning rate too small) necessitating a high number of iterations (epochs).

The linear regression was our starting model. Nature and most dataset are far from being linear! Later in this course, we will see (slightly) more complex machine learning algorithms able to model non-linear behaviour. Linearity is an assumption that should be made with care.

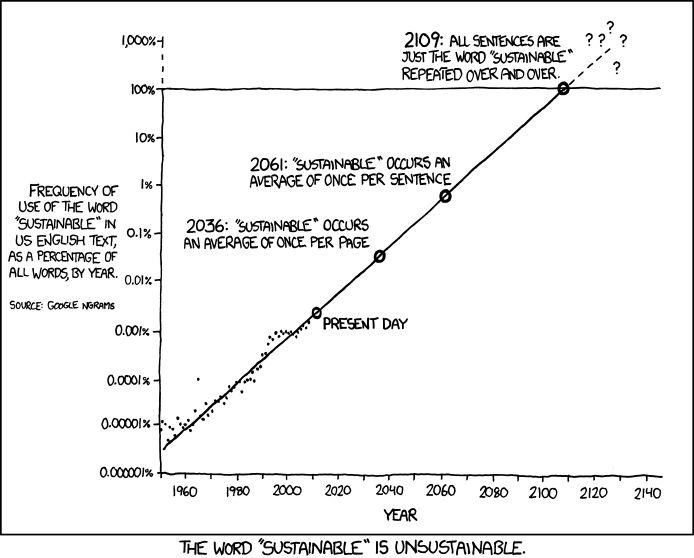

Fig. 10 : A questionable linear extrapolation, from the great webcomic xkcd.#